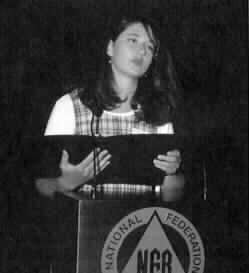

Cheralyn Braithwaite

The Blind in the Teaching Profession

by Cheralyn Braithwaite

**********

From the Editor: The first item on the Thursday morning

agenda at the 1998 National Convention was a presentation by

Cheralyn Braithwaite, a special education teacher from Bountiful,

Utah. Her story was familiar, but she told it with compelling

honesty and heart-warming enthusiasm. This is what she said:

**********

I was born to a family of ten children. When I was one year

old, my mom noticed that I held books close to my face and that I

watched TV with my chin on the TV table--there are still teeth

marks on the edge of it to prove it. My dad and some of my

brothers and sisters dismissed it as a bad habit. None of them

wanted me to visit an optometrist for fear we'd find out I was

going to be different, need glasses, and be made fun of. As well

intended as my family was, they were afraid of my vision or the

lack of it.

I fell into that fear by pretending I was no different from

anyone else. We found out that I had "extreme myopia, a lazy eye,

and astigmatism." I got glasses when I was almost two and contact

lenses at four. They helped, but just hid the problem. When asked

if I could see a deer at the side of the road, I pretended I

could. I endured backyard vision screenings, playing catch with a

brother who was convinced that the harder he threw the softball,

the more likely I'd be to see it. When watching a movie or play,

I laughed on the cue of the rest of the audience, pretending I

knew the punch line without admitting I needed an explanation. It

goes on and on. My scheming worked for years--or so I thought. In school I

pretended to read as all the other students did in class. I

pretended I could take the quiz written on the chalkboard or

overhead projector. Although I was a relatively hard-working

student, I allowed my grades to slide and allowed myself to

accept being less than I am. One experience I had during this period of pretending to be

normal still haunts me. I had just proved my ability to perform

in an advanced English class in the seventh grade. The transfer

was made, and soon I was involved in a group presentation on The

Red Badge of Courage. My turn to present came. It was accompanied

by an all too familiar anxiety attack. I looked at my notes and

then at my peers and decided it just wasn't worth the humiliation

of holding the paper at the necessary reading distance, the end

of my nose. Instead, I chose an alternate route to humiliation. I

attempted to read my notes at the normal distance. The student

next to me (as well as the teacher and the rest of the class, I'm

sure) sensed my difficulty. This student began whispering my

notes to me like a parent to a timid child performing for an

audience. I dismissed my frustration with a laugh here and there

between my disjointed prompts. Finally it ended. I hoped I could

now put the experience behind me. But that wasn't possible. The

adolescent devastation was there to stay. My teacher didn't let

it go either. She called my parents to find out if I was able to

read. She thought I wasn't intelligent enough for her class. Dad

made the necessary excuses, and I was able to remain in the

class. Unfortunately the memory also remained. Trying to be

normal wasn't worth the pain. This faking continued until my vision decreased

significantly in my eighth-grade year. The issue could no longer

be ignored. I saw a specialist and was finally given a label. "I

have cone dystrophy," and soon thereafter I was able to say, "I

am visually impaired." The second label came after being

introduced to special education and a dear friend named Carol.

She helped me face my fears of admitting there was a problem and

helped me to make adaptations. This was a huge step in my life. I

no longer allowed anything to keep me from getting straight A's. I still had a lot of learning to do by way of admitting to

myself that I couldn't do things the same way as others around

me. I even got a driver's license. (I guess legally I could

drive, but realistically I was crazy to try--especially when I

cheated on one of the vision tests.) Driving lasted for only a

few years until I'd put myself and others in danger too many

times. Giving it up, as much as I needed to, was devastating. I

remember other periods of devastation, sitting in classes and

other situations with tearful eyes, wondering why I was so stupid

and why couldn't I do things the same way as the students or

friends around me could. All of this in an attempt to be normal.

It too wasn't worth the pain. College wasn't a huge adjustment. I entered Brigham Young

University as a special education major with two scholarships and

the same old insecurities. I learned quickly that I couldn't

depend on Support Services for Students with Disabilities.

Classes weren't easy, so I had to start developing my own

adaptive techniques. With each semester I learned techniques that

would make the next one even easier. I got my own readers; I

learned to rely on descriptions while using binoculars to

distinguish objects in slides or on the board. I figured out that

I can read print on certain colors more easily than on others, so

I began using colored transparency sheets to lay over the page I

was reading. Through this I gained confidence, but I still

avoided computers at all costs. This confidence greatly increased when I came in contact

with Norman Gardner, Ray Martin, and their wives. They introduced

me to the National Federation of the Blind just over two years

ago. They came at just the right time. Relationships, my choice

of major, and other serious decisions in my life left me doubting

myself as I never had before. I was dragged to Anaheim,

California, by Norm and Ray for the 1996 National Convention of

the National Federation of the Blind. It really was quite an ordeal getting me there. I was very

scared. I had never traveled alone; I never did anything alone.

(I went out of my way to plan for family members or friends to be

with me wherever I went. I couldn't even walk into church alone

for fear I wouldn't find the pew where my family sat.) Now this!

Flying alone, navigating an airport alone, claiming baggage

alone, coping with possible transfers alone. My dad never really

liked the idea of my going places alone, and I knew I hated the

idea myself. But I finally consented because there would be other

people whom I had met once before on the same flight, and they

were willing to help me. Although overwhelmed, I soon came to know many people who

have become some of my best friends and role models--Kristen Cox,

Ron Gardner, Robert Olsen, their spouses, and Bruce Gardner. I

began to learn that I had potential that I'd never given myself

credit for and never let others see. I knew I didn't have to be

afraid anymore of who I was. I knew I would be more honest with

myself and be able to let others see the real me. All of these

feelings culminated at the banquet. I had heard all the

incredible plans of the scholarship winners, and I realized I

didn't want to live any of the misconceptions that President

Maurer referred to. Most of all, I knew my life could never be

the same. The pretending and the fear had to end. I went from

doubting my identity, my career choice, and even my self-worth,

to craving independence that I'd never experienced before. In fact, I was accepted to go on a study abroad program to

London. This is where the craving began. By the end of the

program, I was navigating and using the Underground or Tube (the

subway system) independently. I loved the freedom of getting from

place to place, experiencing the culture, etc., with the group or

on my own if I wanted to. Just one year after Anaheim I had school schedule conflicts

that caused me to have to leave a few days late for last year's

National Convention in New Orleans. This meant flying alone,

transferring alone, claiming baggage alone, and getting to the

hotel alone. This time, however, I had a much different

experience. I looked at it as an opportunity and adventure to

test some of my new travel skills and self-reliance. My friend

Norm described it as an example of personal triumph and

independence. What a contrast to the previous year. That

convention only reinforced and intensified the feelings from the

year before. Back to school now. As required at BYU, I had opportunities

to volunteer and later to teach in different classroom settings

each semester in the special education program. I encountered

frightening, stressful, and even dangerous situations. But, as my

mom likes to remind me, a thought hit me one day near the end of

my college career. I realized that I was capable of handling any

one of these classroom situations. My traveling experience as

well as experiences in my education, soon helped me realize that

I didn't want to be the average blind person with the average

job. . . (I think most of us have heard the quotation). I wanted

to be the best! Doing the best job! Before I found this determination, I had been terrified. I

was convinced that I was crazy to think I could be a teacher. I

dreaded applying for jobs because I just knew I would be a joke,

walking into any interview. I had begun to talk myself into

settling for a teacher's assistant position. That way I wouldn't

have to be as responsible and could just follow in someone else's

footsteps. But, as I said, my introduction to the NFB came at just the

right time. I began using a cane (after leaving my lasting

impression in college when I missed the barricades and stepped

into fresh cement on campus), and I also began learning how to be

up-front about my blindness in professional situations. I

absolutely hated the interviewing process, but I kept at it.

Suddenly the terror ended when I interviewed with some very open-

minded people. I was amazed to find that I wouldn't be turned

down because of a disability but instead that I was hired, not

only because of my accomplishments, but also because of the

determination and sensitivity my blindness has given me. Soon I

found myself tearfully saying good-bye to my parents (both

natural and in the Federation) to accept a position an hour away

in a junior high intellectually disabled unit. Here was the

independence I'd longed for. I am fortunate enough to have a boss who is very sensitive

to the needs of his teachers. He knew there was a possibility

that I'd need some adaptive technology. So for Christmas he gave

me a request form for the things I needed. Now I have a large

computer monitor (my jumbo tron), with speech and enlargement

software on the way (I can't survive without the one thing I

hated and dreaded in school--I'd die without my computer), and I

also have a lighting system in my classroom that dims above my

desk to make my reading and paper work more bearable. I am also fortunate to work with amazing teachers who are

willing to support and help each other whenever needed. They

aren't condescending in their offers to help. But I think they

are still learning about me as an individual and about blindness

in general. (I really confused them when I won the turkey at the

Thanksgiving faculty free throw contest.) It's hard to believe I ever considered being merely a

teacher's assistant. I now have two full-time assistants and one

part-time assistant working under me. I also supervise several

students who get credit for being peer tutors in my classroom. My

assistants understand my limitations (not seeing problem

behaviors at the back of the room, etc.) and are able to follow

my cues to deal with such situations. They know that I'm in

charge, and I'm able to give them unique responsibilities that

they might not have in a sighted teacher's classroom. I find that

this brings accountability and consistency to my classroom. I can even recognize ways that my students benefit from my

blindness. I'm sensitive to their feelings of inadequacy. I'm

able to come up with alternative ways of learning the same thing.

The concepts they learn are practiced and reinforced since I have

to ask them to read or tell me what they are working on or what

their answer is. I'm not afraid to admit, and even laugh, when I

make a mistake. I absolutely love my job! I never expected to enjoy being a

professional so much. It wasn't an easy road getting to this

point, and I know the journey continues. I know I owe much of

this to my involvement in the National Federation of the Blind.

It was this organization that helped me gain confidence, self-

respect, initiative, and courage to do the things I've mentioned.

I was strengthened by the philosophy, the history I learned from

reading Walking Alone and Marching Together, the leadership, the

political influence I witnessed at Washington Seminar, etc. I

will forever be grateful for what I have gained and will continue

to gain from the NFB and the people and philosophy that make it

what it is. I now hope to bring it to others so that it can

dramatically change their lives too. Thank you.

**********https://nfb.org/images/nfb/publications/bm/bm98/bm981204.htm

留言

張貼留言